Model

The oleic acid induction system Model

Mechanism

Oleic acid → acyl-CoA A → FadR protein departs from promoter PfadB → gene expresses normally, β-oxidation initiates.

Without oleic acid → FadR protein binds to promoter PfadB → gene expression is inhibited.

From the oleic acid induction mechanism, we can divide the expression of the FadR promoter into the following two scenarios:

The balance of oleic acid synthesis metabolism and decomposition metabolism in microorganisms is controlled by the transcriptional regulatory factor FadR. In the absence of oleic acid, it's a Growth phenotype with native negative autoregulation (NAR) . At this time, fatty acid synthesis metabolism is activated. FadR binds to the promoter p-fadB of the bacterial β-oxidation pathway gene fadO, inhibiting the expression of fadO, thereby inhibiting bacterial β-oxidation. In the presence of excess oleic acid, it's a Production phenotype with engineered positive autoregulation (PAR) . Fatty acid degradation metabolism is activated. After FadR couples with oleic acid, it departs from the promoter p-fadB of fadO, allowing fadO expression, and bacterial β-oxidation is completed.

Model Assumptions

1. The activation state of the oleic acid inducer (corresponding to the presence/absence of oleic acid environment) can be determined by the concentration of the regulator FadR. The expression of the product synthesis enzyme and the synthesis of the product itself depend on the control factor FadR. Therefore, we only define the state of the oleic acid inducer by the concentration of FadR.

2. FadD expression is solely controlled by FadR. In native E. coli, the expression of FadD under aerobic conditions is co-regulated by FadR and the CRP-cAMP complex (EcoCyc). However, in the presence of common carbon sources like glucose, the expression level of CRP-cAMP is very low, so its effect can be neglected.

3. The expression rate of the enzyme in two oleic acid inducer states can be modeled in the form of a Hill function. Studies have shown that the expression of gene products takes the form of a Hill function [4], either as $P_T(T)=\frac{a \cdot(K \cdot T)^n}{1+(K \cdot T)^n}$ for $T$-activated expression, or as $P_T(T)=\frac{a}{1+(K \cdot T)^n}$ for $T$-inhibited expression, where $a$ is the maximum expression rate, $K$ is the affinity with which transcription factor $T$ binds to the operator and controls expression, and $n$ is the Hill coefficient.

4. The growth rate of engineered bacteria linearly depends on the growth-related enzyme Eg. According to research by Usui et al. [3], the cell growth rate decreases in an approximately linear fashion. We capture this phenomenon and define the growth rate of the cell using a linear function as follows: $\lambda\left(E_g\right)=E_g \cdot \lambda_{\min }+\left(\lambda_{\max }-\lambda_{\min }\right)$. Where $\lambda_{\min }$ and $\lambda_{\max }$ represent the growth rates at zero and maximum expression of $E_g$, respectively.

5. Enzymes and transcription factors do not undergo active degradation. To our knowledge, proteins in the system we study are not actively degraded. Over the duration of cell doubling, protein dilution through cell growth and division is the main way proteins are lost from the system, so we model the decay of protein $E$ as growth dilution $\lambda \cdot E$:

Model Establishment

Our endogenous system model is inspired by the model of Ahmad A. Mannan et al.[1] and the model of Hartline et al.[2], which models the expression rates of the transcription factor FadR, uptake enzyme FadD, and growth-related enzyme $E_g$ [5] using Hill functions as $r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{R}}=P_{\mathrm{R}}(R), r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{D}}=P_{\mathrm{D}}(D)$, $r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{E}_{\mathrm{g}}}=P_{\mathrm{g}}\left(g\right)$. The reaction kinetics of FadD $\left(r_{\mathrm{D}}\right)$ and the reaction kinetics of the acyl-CoA-consuming reaction PIsB $\left(r_{\mathrm{B}}\right)$ are modeled as Michaelis-Menten equations, resulting in:

$$

\begin{aligned}

& r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{R}}=b_{\mathrm{R}}+P_{\mathrm{R}}(R),

\quad r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{D}}=b_{\mathrm{D}}+P_{\mathrm{D}}(D),

\quad r_{\mathrm{x}, E_{\mathrm{g}}}= P_{\mathrm{g}}(g)\\

& r_{\mathrm{D}}=\frac{k_{\mathrm{cat}, \mathrm{D}} \cdot \mathrm{OA}}{K_{\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{D}}+\mathrm{OA}} \cdot D, \quad r_{\mathrm{B}}=\frac{k_{\mathrm{cat}, \mathrm{B}} \cdot A}{K_{\mathrm{m}, \mathrm{B}}+A} \cdot B .

\end{aligned}

$$

Here, the expression rate of FadR is either the native negative self-regulation (NAR) or the positive self-regulation (PAR) engineered in [2], while the expression rate of FadD remains negative self-regulation (NAR), and the $E_g$ expression rate remains positive self-regulation (PAR):

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \text { NAR : } P_{\mathrm{R}}(R)=\frac{a_{\mathrm{R}}}{1+K_{\mathrm{R}} R}, \\

& \text { PAR : } P_{\mathrm{R}}(R)=\frac{a_{\mathrm{R}} K_{\mathrm{R}} R}{1+K_{\mathrm{R}} R} \\

& \text { NAR : } P_{\mathrm{D}}(D)=\frac{a_{\mathrm{D}}}{1+\left(K_{\mathrm{D}} R\right)^2}, \\

& \text { PAR : } P_{\mathrm{g}}(g)=\frac{a_{\mathrm{g}} K_{\mathrm{g}} R}{1+K_{\mathrm{g}} R} .

\end{aligned}

$$

Additionally, we use the mass-action kinetics model to describe the rate of formation of $[R][A]_2$ due to the sequestration of FadR by two molecules of acyl-CoA, as given by the following equation:

$$

r_{\mathrm{seq}}=r_{\mathrm{f}}-r_{\mathrm{r}}=k_{\mathrm{f}} A^2 R-k_{\mathrm{r}} C

$$

We now extend the model of Hartline and Mannan to simulate its application in oleic acid-inducible control over growth and production. The expression of product synthesis enzymes and the product itself does not provide feedback that affects the rest of the control system. Since it relies solely on FadR, we do not explicitly model production. Instead, using the same approach as in [1], we define the native production phenotype by a low set concentration value of FadR $R \leq 0.0033 \mu \mathrm{M}$. This implies that the growth phenotype of the engineered bacteria activated by the oleic acid inducer is defined as $R>0.0033 \mu \mathrm{M}$.

During the experimental process, we added the gene of the green fluorescent protein after the oleic acid inducer operator fadO. When FadR binds to the operator fadO, leading to the activation of the oleic acid inducer, the green fluorescent protein gene is expressed. Therefore, by detecting the intensity of the green fluorescent protein $F$ in the culture medium, we can assess the activation level of the oleic acid inducer, that is:

$$

F = K_p \cdot \int_0^T r_{\text {seq }}\left(t\right) d t+ b_p

$$

Now, we establish the ordinary differential equation model for the change rates of FadR(R), FadD (D), acyl-CoA (A), sequestered complex (C), growth-associated enzyme(Eg), and fluorescent protein(F):

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{d R}{d t} & =r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{R}}-r_{\mathrm{seq}}-\lambda\left(E_{\mathrm{g}}\right) R, \\

\frac{d D}{d t} & =r_{\mathrm{x}, \mathrm{D}}-\lambda\left(E_{\mathrm{g}}\right) D, \\

\frac{d A}{d t} & =r_{\mathrm{D}}-r_{\mathrm{B}}-2 \cdot r_{\mathrm{seq}}-\lambda\left(E_{\mathrm{g}}\right) A, \\

\frac{d C}{d t} & =r_{\mathrm{seq}}-\lambda\left(E_{\mathrm{g}}\right) C, \\

\frac{d E_{\mathrm{g}}}{d t} & =r_{\mathrm{x}, E_{\mathrm{g}}}-\lambda\left(E_{\mathrm{g}}\right) \cdot E_{\mathrm{g}}, \\

\frac{d F}{d t} & =r_{\mathrm{seq}}.

\end{aligned}

$$

Model Simulation

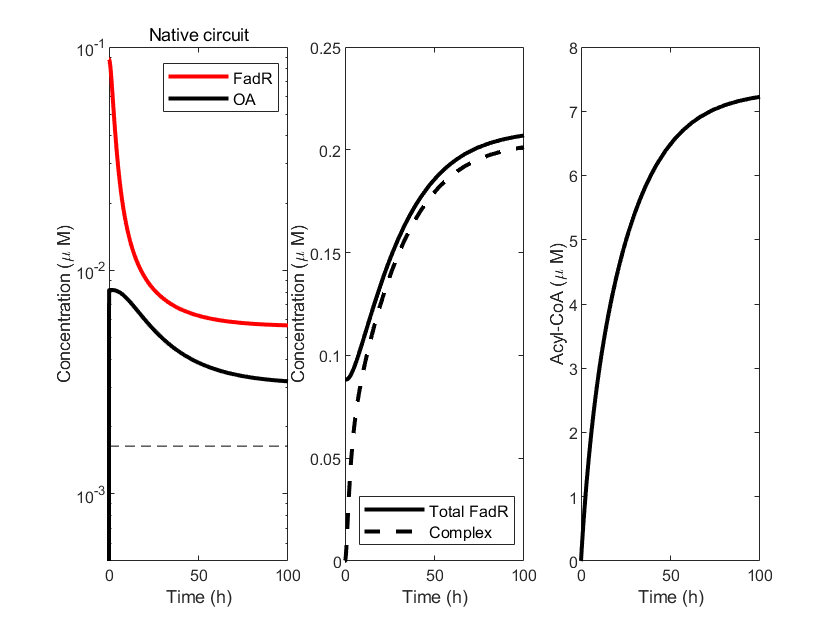

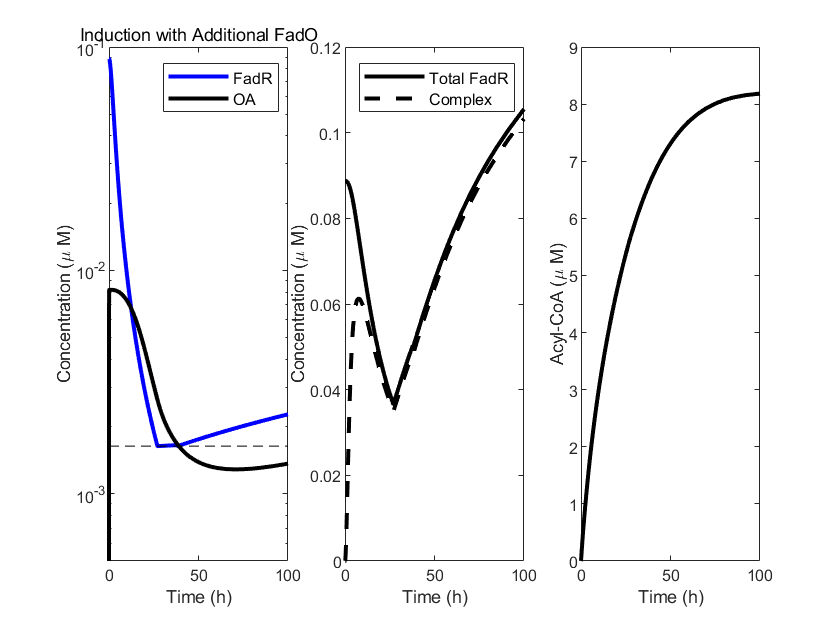

To validate the feasibility of the above model, we wrote the corresponding model code in Matlab, simulating the continuous introduction of oleic acid (OA). The selection of model parameters was based on data from references [1,2]. We simulated the temporal changes of model variables under the conditions of natural circuits (red curve) and engineered oleic acid inducer circuits (blue curve). In the first subplot, we compared the concentrations between FadR(R) and OA, where the black dashed line represents the activation threshold of the oleic acid inducer. The second subplot compares the relationship between Total FadR and the sequestered complex (C). The third subplot reflects the concentration of acyl-CoA (A) over time.

From the figures, it can be observed that the introduction of the oleic acid inducer accelerates the decomposition process of OA, causing its concentration to decrease at a faster rate, which also proves the effectiveness of the oleic acid inducer.

Model expansion with additional FadO operators

By modifying a segment of the FadO operator sequence in the promoter region, we can alter the oleic acid concentration threshold required to activate the promoter. Specifically, increasing the FadO operators raises the threshold of oleic acid needed for acyl-CoA to dissociate from FadR, allowing the PfadBPfadB promoter to initiate transcription normally. This mechanism sets a higher bar for oleic acid inducer activation. With this approach, through quantitative experimentation and mathematical modeling, we can determine the appropriate induction initiation threshold range, which aligns with the oleic acid content defined in high-fat diets for various individual physiologies. Consequently, this allows us to design cholesterol-degrading bacterial strains based on the oleic acid inducer principle, tailored to fit the gut nutritional environment of different individuals.

Similarly, we conducted model simulations to verify the feasibility of the aforementioned operation. Specifically, we utilized an alternative approach, adjusting the affinity of FadR to inhibit Ep synthesis within our system, to emulate the effects of modifying the FadO operators. A higher affinity mimics the impact of having additional FadO operators, necessitating a higher oleic acid concentration to activate the promoter, and vice versa.

In the model simulation graphs, we observe that compared to the original oleic acid inducer, the new version with added FadO operators delays the decomposition rate of OA. At the same time, the threshold at which the oleic acid inducer activates FadR is lower. Given that acyl-CoA (A) reacts with FadR, this suggests that a higher threshold of oleic acid decomposition is required to produce acyl-CoA (A). This is consistent with our theoretical predictions. The results validate that by increasing the FadO operators, we can precisely control the response threshold of the oleic acid inducer, making it adaptable for different scenarios.

References

[1] Mannan, A.A., Bates, D.G. Designing an irreversible metabolic switch for scalable induction of microbial chemical production. Nat Commun 12, 3419 (2021).

[2] Hartline, C., Mannan, A., Liu, D., Zhang, F. & Oyarz´un, D. Metabolite sequestration enables rapid recovery from fatty acid depletion in Escherichia coli. mBio (2020).

[3] Usui, Y. et al. Investigating the effects of perturbations to pgi and eno gene expression on central carbon metabolism in Escherichia coli using 13 C metabolic flux analysis. Microbial Cell Factories 11, 1–5 (2012).

[4] Mannan, A. A., Liu, D., Zhang, F. & Oyarz´un, D. A. Fundamental design principles for transcription-factor-based metabo-lite biosensors. ACS Synthetic Biology 6, 1851–1859 (2017).

[5] Janßen, H. J. & Steinb¨uchel, A. Fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli and its applications towards the production of fatty acid based biofuels. Biotechnology for biofuels 7, 7 (2014).

[6] Marino, S., Hogue, I. B., Ray, C. J. & Kirschner, D. E. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. Journal of Theoretical Biology 254, 178–196 (2008).

[7] Bertram, R. & Hillen, W. The application of Tet repressor in prokaryotic gene regulation and expression. Microbial Biotechnology 1, 2–16 (2008).

[8] Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer (2020). URL https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer.

[9] Kamionka, A., Bogdanska-Urbaniak, J., Scholz, O. & Hillen, W. Two mutations in the tetracycline repressor change the inducer anhydrotetracycline to a corepressor. Nucleic Acids Research 32, 842–847 (2004).

[10] Gardner, T. S., Cantor, C. R. & Collins, J. J. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature 403,339–342 (2000).

[11] Xu, J. & Matthews, K. S. Flexibility in the Inducer Binding Region is Crucial for Allostery in the Escherichia coli Lactose Repressor. Biochemistry 48, 4988–4998.