Background

Genetic Diseases: A Global Challenge

Genetic diseases occur when changes in our DNA disrupt how genes function, leading to abnormal or missing proteins. These conditions cover a wide range of consequences from disorders caused by a single gene mutation to complex diseases involving many genes and environmental factors. While each rare genetic disease affects only a small number of people, together they impact more than 300 million individuals worldwide 1. Advances in DNA sequencing now allow us to identify the exact genetic causes of most single-gene disorders, but turning this knowledge into effective therapies remains challenging in modern medicine 2.

Traditional treatments, such as giving patients the missing protein, enzyme replacement, or small-molecule drugs, often help with symptoms but don’t fix the root cause: the faulty DNA. Gene-based therapies aim to do exactly that by repairing or replacing the defective gene itself. Over the past decade, tools like ZFNs, TALENs, and especially CRISPR/Cas9 have transformed this field by allowing precise editing of DNA sequences. These “molecular scissors” can cut DNA at a chosen site, enabling correction or replacement of short sequences. In some cases, CRISPR-based approaches have already achieved cures for single-gene diseases 3.

However, there are still hurdles: limited efficiency in non-dividing tissues like neurons or liver cells, potential off-target edits, and challenges in safely delivering these tools into the body. Moreover, most current editors are suited for fixing single-base errors or small insertions, but not for replacing large or complex sections of DNA 3.

Gene editing is therefore both a scientific frontier and a medical opportunity. The ability to repair disease-causing mutations directly at their source could lead to long-lasting cures. Yet, for broad clinical use, we need technologies that go beyond one mutation at a time — systems that can replace or restore entire genes regardless of the underlying mutation.

The Economic Challenge of Genetic Medicines

Developing gene therapies is not only scientifically difficult but also economically demanding. Most current editing platforms are designed for a single mutation, meaning that each therapy serves only a very small patient group. This limited reach makes it hard to justify the enormous costs of research, manufacturing, and clinical trials 4.

To make genetic therapies more affordable and accessible, new approaches are needed. Ones that can correct multiple mutations within the same gene using a single therapeutic design. Technologies that enable allele-independent gene correction could transform the economics of this field. If one construct could restore normal gene function across many different variants, the potential patient base would grow dramatically, making treatment development more sustainable while giving more patients access to curative options.

Bridge Recombinases: A New Class of Programmable Genome Editors

Bridge recombinases are a newly discovered family of genome-editing enzymes that share some important similarities with CRISPR systems but also introduce key new capabilities 5.

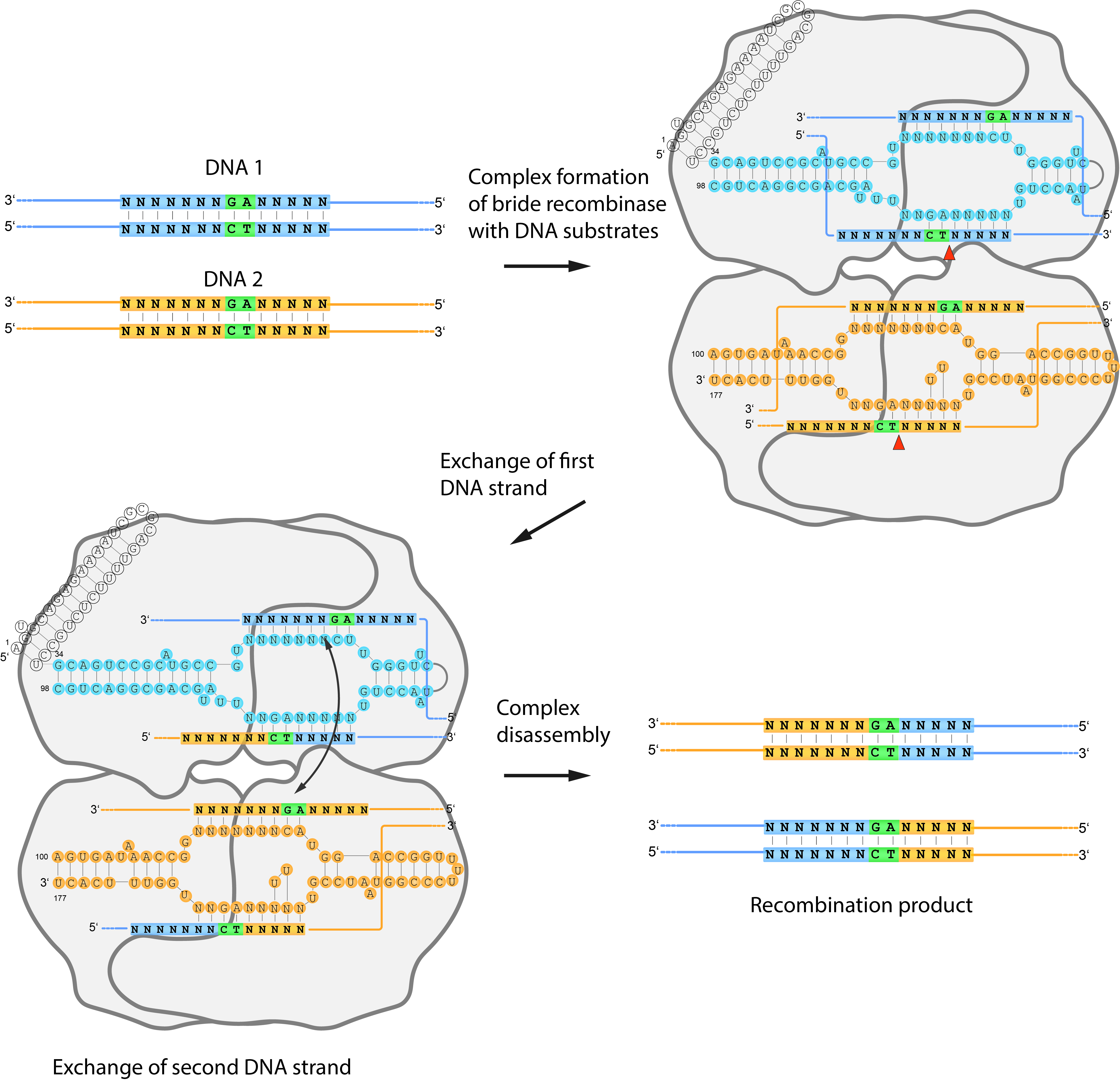

Like CRISPR/Cas9, bridge recombinases use an RNA molecule to guide them to a specific DNA sequence. In CRISPR, this is the guide RNA (gRNA), which directs Cas9 to make a precise cut in the DNA. In bridge recombinases, the guiding element is a bridge RNA (bRNA) — but instead of simply guiding the enzyme to the correct site in the genome, it helps connect two pieces of DNA 6.

Each bridge recombinase combines a DEDD-family recombinase enzyme with its structured bridge RNA. The bRNA contains two short loops that base-pair separately with (1) a genomic target site and (2) a donor DNA carrying the new genetic information. This dual binding brings both DNA molecules into alignment so the recombinase can join them together at specific sites 5.

Through this mechanism, bridge recombinases can perform three fundamental operations: insertion, deletion, and inversion of DNA fragments, all without making double-stranded breaks or depending on the cell’s natural repair machinery. This sets them apart from CRISPR, which relies on DNA cleavage followed by repair through pathways such as NHEJ or HDR 5.

Because their targeting is dictated by RNA–DNA pairing, bridge recombinases are programmable and modular, much like CRISPR. By simply changing the sequence of the bridge RNA, researchers can redirect the enzyme to a new genomic site. However, bridge recombinases expand the concept of RNA-guided editing into a new domain: they can integrate large DNA fragments (kilobases in length) with high precision, something CRISPR-based tools struggle to achieve efficiently 5.

So far two bridge recombinases, IS621 and ISCro4, have been characterized. They share about 88% sequence identity, suggesting that many other natural variants likely exist, some potentially even more efficient. Both of these enzymes have shown that RNA-guided recombination works reliably: IS621 functions well in bacteria, and ISCro4 in mammalian cells. Together, they define a new and powerful class of RNA-programmable genome editors that could overcome many limitations of existing technologies 6.

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency as a Proof of Concept

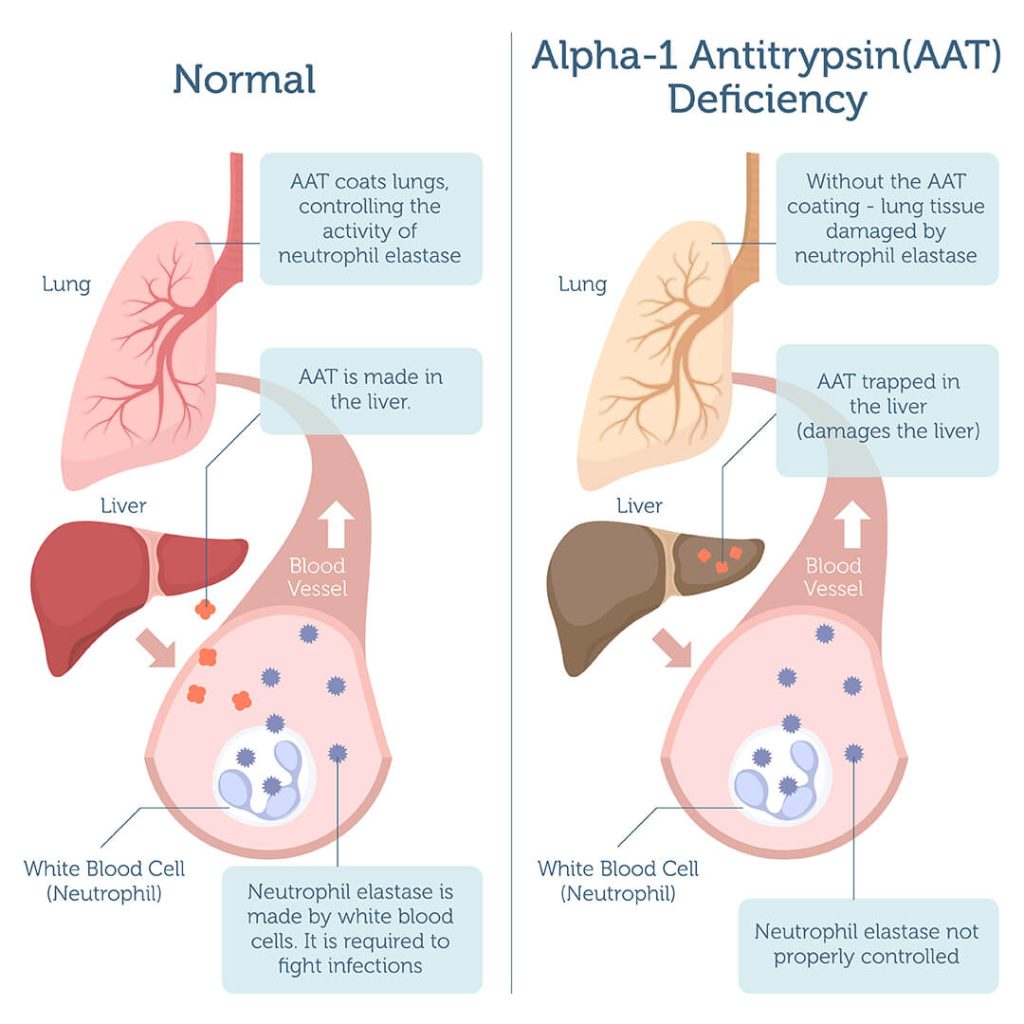

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (A1ATD) is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the SERPINA1 gene. These mutations lead to low levels or misfolding of the α1-antitrypsin protein, a key molecule that protects the lungs and liver from damage. More than 150 disease-causing variants of SERPINA1 have been identified, including the common S (Glu264Val) and Z (Glu342Lys) variants, along with many rare mutations. Because so many different mutations can cause the same disease, A1ATD is a perfect model for testing broad, multi-allelic gene correction strategies 7.

Clinically, A1ATD often goes undiagnosed because its symptoms overlap with other conditions such as asthma, COPD, or chronic liver disease. The disease manifests as lung damage (due to lack of functional α1-antitrypsin) and liver injury (due to accumulation of misfolded protein in hepatocytes) 8.

Recent work by Beam Therapeutics has shown that delivering genetic medicines directly into the liver using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) can restore α1-antitrypsin expression in humans to therapeutic levels. This demonstrates that enough liver cells can be genetically corrected in vivo to cure the disease, making A1ATD an ideal proof-of-concept model for testing new editing systems 9.

In this context, bridge recombinase–based therapy could offer a universal solution. By inserting a healthy copy of the SERPINA1 gene directly into its natural location in the genome, this method could restore function no matter which mutation caused the disease, a single treatment for all variants.

Our IDEC 2025 Project: Evolving Bridge Recombinases

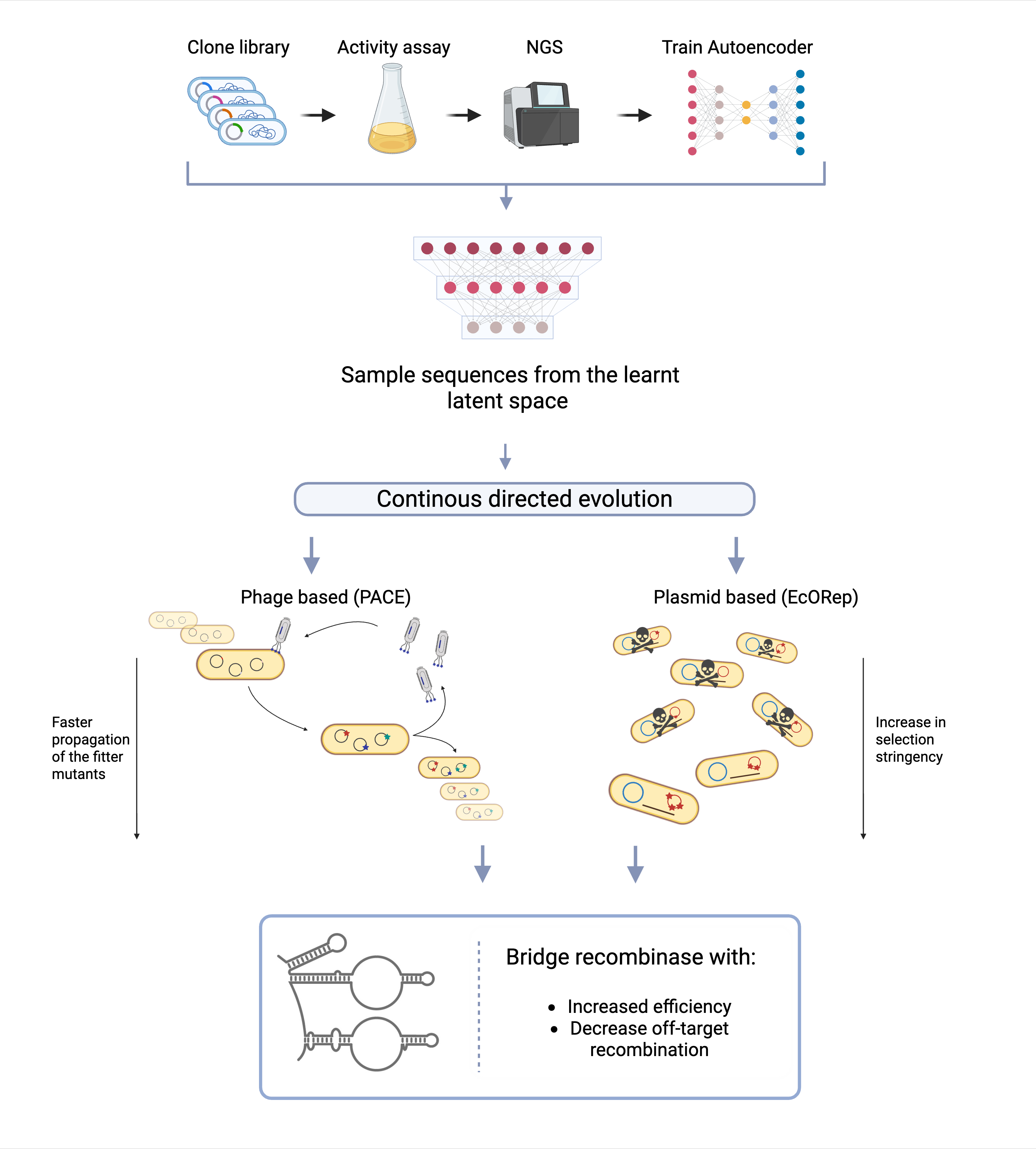

In our 2025 IDEC project, we aim to push bridge recombinases beyond their natural limits. Our team is developing a directed evolution strategy to improve both their efficiency and specificity. Building on the known IS621 and ISCro4 enzymes, we are combining deep mutational learning (DML)10 with two continous evolution systems: • E. coli Orthogonal Replication (EcORep) 11 • Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) 12

Our goal is to map and understand the fitness landscape of bridge recombinases — essentially, how different mutations affect their activity, and evolve versions that are better at inserting large DNA fragments precisely and efficiently.

As a proof of principle, we focus on Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (A1ATD). If we can use an evolved bridge recombinase to replace the faulty SERPINA1 gene with a healthy one, it would demonstrate a powerful new way to correct genetic diseases at their root — and potentially make large-scale, mutation-independent cures a reality.

References

-

Li T, Yang Y, Qi H, Cui W, Zhang L, Fu X, He X, Liu M, Li P, Yu T. CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023;8:36. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01309-7 ↩

-

Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2016;17:333–351. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.49 ↩

-

Pacesa M, Pelea O, Jinek M. Past, present, and future of CRISPR genome editing technologies. Cell. 2024;187(5):1076–1100. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.012 ↩↩

-

Kliegman M, Zaghlula M, Abrahamson S, Esensten JH, Wilson RC, Urnov FD, Doudna JA. A roadmap for affordable genetic medicines. Nature. 2024;634:307–314. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07561-8 ↩

-

Durrant MG, Perry NA, Pai JJ, Jangid AR, Athukorallage JS, Hiraizumi M, McSpedon JP, Pawluk A, Nishimasu H, Konermann S, Hsu PD. Bridge RNAs direct programmable recombination of target and donor DNA. Nature. 2024;630:984–993. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07540-z ↩↩↩↩

-

Perry NA, Bartie LJ, Katrekab D, Gonzalez GA, Durrant MG, Pai JJ, Fanton A, Martins JD, Hiratsumi M, Hsu PD. Megabase-scale human genome rearrangement with programmable bridge recombinases. Science. 2025; First Release. doi:10.1126/science.adx0726 ↩↩

-

Greene CM, Marciniak SJ, Teckman J, Ferrarotti I, Brantly ML, Lomas DA, Stoller JK, McElvaney NG. α1-Antitrypsin deficiency. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2016;2:16051. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.51 ↩

-

Strnad P, McElvaney NG, Lomas DA. Alpha1-Antitrypsin Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382:1443–1455. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1910234 ↩

-

Beam Therapeutics. Breaking new ground to advance science with precision genetic medicines. https://beamtx.com/ (accessed 2025-10-6). ↩

-

Frei L, Gao B, Han J, Taft JM, Irvine EB, Weber CR, Kumar RK, Eisinger BN, Ignatov A, Yang Z, Reddy ST. Deep mutational learning for the selection of therapeutic antibodies resistant to the evolution of Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2025;9:552–565. doi:10.1038/s41551-025-01326-5 ↩

-

Tian R, Rehm FBH, Czernecki D, Gu Y, Zürcher JF, Liu KC, Chin JW. Establishing a synthetic orthogonal replication system enables accelerated evolution in E. coli. Science. 2024;383(6681):421–426. doi:10.1126/science.adk1281 ↩

-

Miller SM, Wang T, Liu DR. Phage-assisted continuous and non-continuous evolution. Nature Protocols. 2020;15:4101–4127. doi:10.1038/s41596-020-00424-4 ↩