Results

Selection of of the E3 ligase

After evaluating several well-known human E3 ligases that could be engineered, we decided to work on evolving SIAH1 and SIAH2 (collectively referred to as SIAH1/2 in this text), which are primarily associated with cellular stress response, such as hypoxia12. Both belong to the RING family of E3 ligases and share 86% sequence identity with nearly identical substrate-binding domains3. Their small sizes—282 amino acids for SIAH1 and 324 for SIAH2—are optimal for phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE), as this allows for efficient expression in E. coli and packaging into M13 bacteriophages. Moreover, this small size compared to other E3 ligases also reduces the theoretical library size which is usually advantageous in directed evolution experiments. In general, neither SIAH1 nor SIAH2 are individually characterised to the extent we would like them to be but together they generate a full picture. SIAH2 has already been used successfully in E. coli ubiquitination assays without any partner proteins except E1 and E2, suggesting that additional regulatory proteins aren’t required for its ubiquitination activity4. This streamlines the evolution processes by reducing potential points of failure in the selection system and keeps the plasmid sizes within an acceptable range. Given how similar SIAH1 is to SIAH2 in structure and function, we anticipate it will behave similarly in E. coli as well. While these studies are missing for SIAH1, the binding of SIAH1 to specific peptide sequences has been well-studied via X-ray crystallography56, which is missing for SIAH2. Together, the data available for SIAH1/2 offer a solid foundation for targeting new sequences and evolving either protein to recognize non-canonical substrates.

The SIAH family recognizes its targets through a PXAXVXP degron motif7, where conserved residues Pro, Ala, Val, and Pro face the SIAH binding pocket (Figure 1). Specificity is mainly determined by the Ala and Val residues in positions 3 and 5, as these pockets are too small to accommodate larger side chains8. Additionally, the Pro residue at position 7 interacts with Trp178 in SIAH, contributing further specificity. Among canonical substrates, the VXP sequence is highly conserved69, while other residues show more variability, making them prime candidates to alter SIAH1/2 specificity for these positions.

Selection of SIAH1/2 canonical targets

The selection of canonical SIAH1/2 targets, needed to test the evolution logic, was performed based on the following criteria:

- The canonical substrate should be mainly cytoplasmic and not inserted or localised near the plasma membrane or in other cell organelles.

- The canonical substrate should not natively form di- or other multi-mers as this could interfere with the selection system by tying two or more C-terminal RNAP subunits together.

- Post-translational modifications (PTMs) on the canonical substrate should not be necessary for its ubiquitination, as we cannot specifically control PTMs of substrates.

- The size of the canonical substrate should not exceed 300 amino acids in size, as this could also compromise our synthetic evolutionary system

- The structure of the protein and interaction with the selected E3 ligase (SIAH1/2) should be characterised.

Based on these five criteria, we searched published ubiquitination databases1112 for canonical substrates. EGLN1, EGLN3 and ɑ-Synuclein were selected as canonical substrates from the mentioned databases as they matched our criteria the best.

| Canonical substrate | Protein size (aa) | Degron | Ubiquitination site | Canonical E3 ligase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGLN3 | 239 | 176-ADVEP-180 | K(159,172) | SIAH1/2 |

| EGLN1 | 426 | 69-VGP-72, 376-VQP-379* | K256 | SIAH1/2 |

| ɑ-Synuclein | 140 | 118-VDP-120 | K(6,10,12,21,23,32,34) | SIAH1/2 |

*For EGLN1 accurate degron was not identified, though two VXP motifs exist of which at least one should act as SIAH1/2 degron.

ɑ-Synuclein is well known for causing Parkinson's disease (PD) and multiple systems atrophy (MSA). Therefore, optimization of SIAH1/2 binding to ɑ-Synuclein could be an attractive alternative evolution strategy in case reprogramming SIAH1/2 specificity does not work as planned.

NLRP3 was selected as an evolutionary target, for its mentioned clinical relevance in hepatic and neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, NLRP3 is an attractive target as it contains two VXP motifs (at positions 200 and 707), located in disordered regions on the surface of NLRP3 (Figure 2). This motif seems to be highly conserved among canonical SIAH1/2 substrates. Therefore, we assume our target choice is limited to proteins naturally displaying this motif on its surface, while other residues involved in binding could be changed. This would allow an evolution of SIAH1/2 to adapt for recognizing different VXP surrounding residues while retaining the conserved VXP binding motif. Furthermore, lysins are found within the VXP surrounding residues, which are needed for ubiquitination. Remarkably, one of these lysins (K689) is natively polyubiquitinated and leads to the canonical degradation of NLRP310, hence suggesting that polyubiquitination of K689 is a viable strategy for inducing NLRP3 degradation. With 1036 amino acids and its potential for oligomerization, NLRP3 could constrain our evolutionary system. Thus two peptide fragments of NLRP3 containing the VXP motif as well as surrounding residues were incorporated in the selection system.

Development of an E3 ligase PACE evolutionary system

Ubiquitination-dependent selection logic

To evolve the SIAH1/2 E3 ubiquitin ligases using the PACE system, we needed to link the ligase’s activity directly to phage propagation. To achieve this, we utilised a modified T7 bacteriophage RNA polymerase (RNAP) that had been split into two halves. Normally, this split RNAP is inactive unless both halves are brought close together within the cell, forming a complete, functional complex. We designed a system where the RNAP halves would only assemble if the E3 ligase successfully ubiquitinated its target.

In this setup, one half of the RNAP is fused to ubiquitin, while the other half is fused to a substrate that can be ubiquitinated. If SIAH1/2 (E3) ubiquitinates the substrate, the two RNAP halves are brought close enough to combine, forming a complete RNAP capable of transcribing genes. We took advantage of this by placing the gene gIII (coding for pIII, a protein crucial for phage propagation) under the control of a T7 promoter, which only the assembled RNAP can activate. As a result, phages can only propagate if SIAH1/2 effectively ubiquitinates the target, tying the phage’s propagation to the ligase’s activity (Figure 3a). Additionally, we also designed a system that could select against specific off-target effects (Figure 3b). To this end, we would add an additional genetic circuit which ‘punished’ E3 ligases that recognised unwanted targets. Instead of the substrate towards which we want to evolve, we fuse the unwanted protein (dubbed the mock substrate) to the C-terminal RNAP subunit. This could be the original canonical substrate of the E3 or a protein recognized as an off-target in later stages of the SIAH1/2 evolution. If this mock substrate is recognized by a SIAH1/2 variant it would also trigger the formation of a functioning RNAP through the ubiquitination of the mock substrate. Crucially, the C-terminal RNAP fused to the mock substrate differs from the one present in the positive selection as it does not bind this T7 promoter sequence, but a slightly altered one. This ensures that one can perform the positive and negative selection at the same time. The altered T7 promoter sequence (*PT7; Figure 3) is then recognized by the negative selection RNAP which leads to the transcription of a mock gIII. Phages that incorporate the encoded protein are essentially unable to infect new cells, leading to the washout of phages carrying SIAH1/2 variants that recognize unwanted substrates.

Assembling the PACE system

To implement this system, we split the evolution process across three plasmids (Figure 4). The first plasmid is the selection phage (SP), which carries the SIAH1/2 gene and the phage genome but lacks the gIII, preventing the phage from propagating without the ligase’s activity. The second plasmid, accessory plasmid 1 (AP1), contains the genes for the E1 and E2 enzymes (which are required for ubiquitination but not normally present in bacteria), the N-terminal half of RNAP fused to ubiquitin, and the gIII controlled by the T7 promoter. The third plasmid, accessory plasmid 2 (AP2), contains the substrate fused to the C-terminal half of RNAP.

This modular system allows us to easily swap out the substrate on AP2, enabling it to be applied to different E3 ligases or substrates. It also supports performing “substrate walks,” a process where we incrementally alter the amino-acid sequence of the substrate recognition motif to shift from a canonical target to a novel target of therapeutic interest. By doing this stepwise, we can control the selection pressure and gradually evolve SIAH1/2 to recognize new substrates.

We plan to run this system in a bioreactor to create a continuous evolutionary environment. SIAH1/2 variants that successfully ubiquitinate the changing substrate will enable phage propagation, while less efficient variants are washed out (Figure 4 below). Over time, we can evolve SIAH1/2 to target a novel substrate, potentially demonstrating that directed evolution is a viable strategy for developing highly specific E3 ligases capable of precise targeted protein degradation.

Experimental results

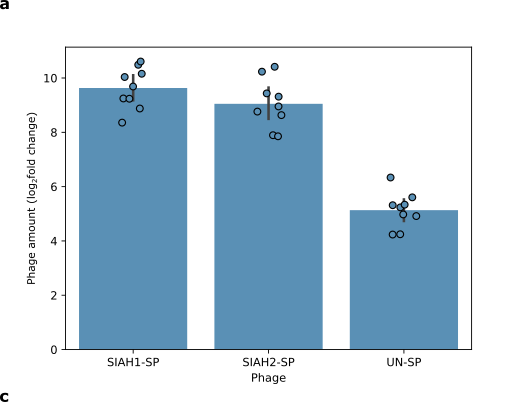

Is phage propagation dependent on the selection phage?

We tested if the E3 ligases SIAH1 and SIAH2 can trigger phage replication when a specific target protein is present. We used the protein EGLN3, which is known to be recognised by SIAH1 and SIAH2. We attached EGLN3 to part of the T7 RNA polymerase enzyme and infected cells with a few phages carrying the SIAH1 or SIAH2 gene. We measured the amount of phage produced after incubating the cells overnight. The phages carrying SIAH1 and SIAH2 replicated more than phages with an unrelated protein (Figure 5). This experiment indicates that our system worked.

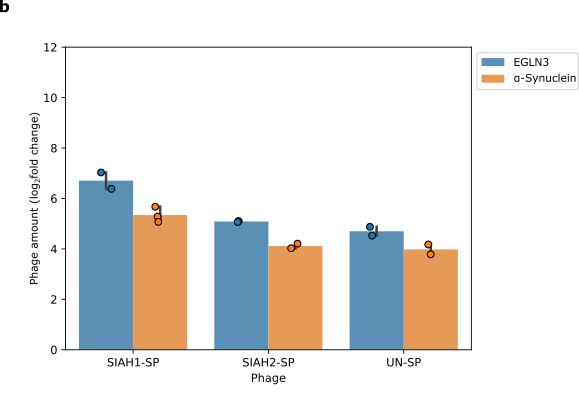

We then looked at whether changing the target protein affects phage replication. We replaced EGLN3 (blue) with α-Synuclein (orange), which is also recognised by SIAH1/2. Changing the target protein changes the level of phage propagation (Figure 6). This shows that our system depends on SIAH1 or SIAH2 and the target protein interacting together.

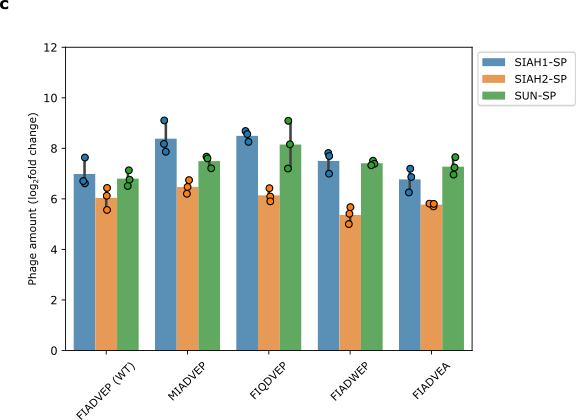

Next, we looked at how changes in the degron would affect our system. We found that even when we altered key parts of the degron in EGLN3, phage replication was not significantly affected (Figure 7). This suggests that phage propagation might be triggered by other factors than the degron.

We were able to show that phage propagation is dependent on both the substrate of the E3 ligase and the E3 ligase itself. However, we also observed a very high background phage propagation in our system. For our evolution to work, we need to be able to link phage proliferation to degron recognition, so this phage proliferation caused by other factors than the degron interferes with the use of this system for the directed evolution part of this project. The next step is to find out why this is happening and how we can modify our system so that it doesn't happen.

What factors lead to unwanted, E3-independent phage propagation?

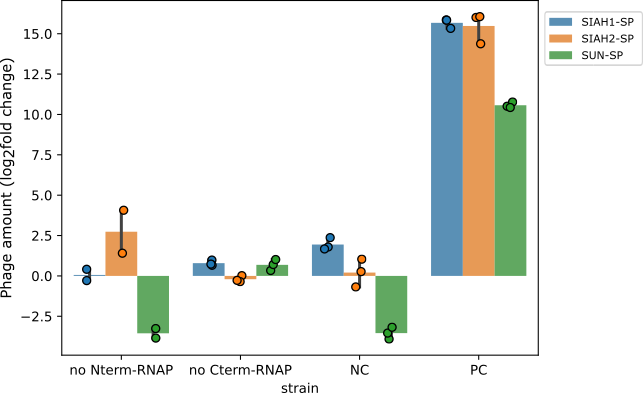

We suspected that the background phage propagation we observed could be caused by one of two things:

- Leaky transcription of gIII: the gene controlling phage growth is turned on without the split-RNAP components being present.

- Spontaneous assembly of the split-RNAP subunits: The two halves of the RNAP are coming together on their own, without the need for ubiquitination of the target substrate.

Both hypotheses lead to gIII expression independent of the E3 ligase activity. To test these hypotheses, we quantified phage propagation in cells that had only one half of the RNAP. In these cells, phage propagation was suppressed, confirming that both halves of the RNAP are required to activate gIII expression (Figure 8). This means that accidental activation of gIII wasn’t the issue. Instead, these results show that the two enzyme halves were probably joining together on their own, causing phage propagation without the involvement of the E3 ligase.

How can we reduce unwanted, E3-ligase-independent phage propagation?

We observed that the RNAP enzyme can assemble and become active before the phages even enter the bacterial cells. This early assembly can lead to unwanted phage propagation, which interferes with our goal to link phage propagation to E3 ligase activity. To overcome this problem, we changed the way we control the production of the N- and C-terminal halves of the RNAP. Instead of using a constitutive promoter, which is always active and produces the protein, we switched to a promoter that can be turned on when needed. For this, we chose two different inducible systems. One is switched on by adding vanillic acid (pVan promoter), the other by the stress response caused by phage infection (phage shock promoter). These new systems let us delay the production of the RNAP halves until just before or during phage infection. By regulating when these components are expressed, we can reduce the unintended assembly of the RNAP. This method can easily be added to the PACE system, allowing precise control of the timing of RNAP production. Experiments with this improved system are currently being performed.

Enhancing SIAH1 genetic diversity using drift.

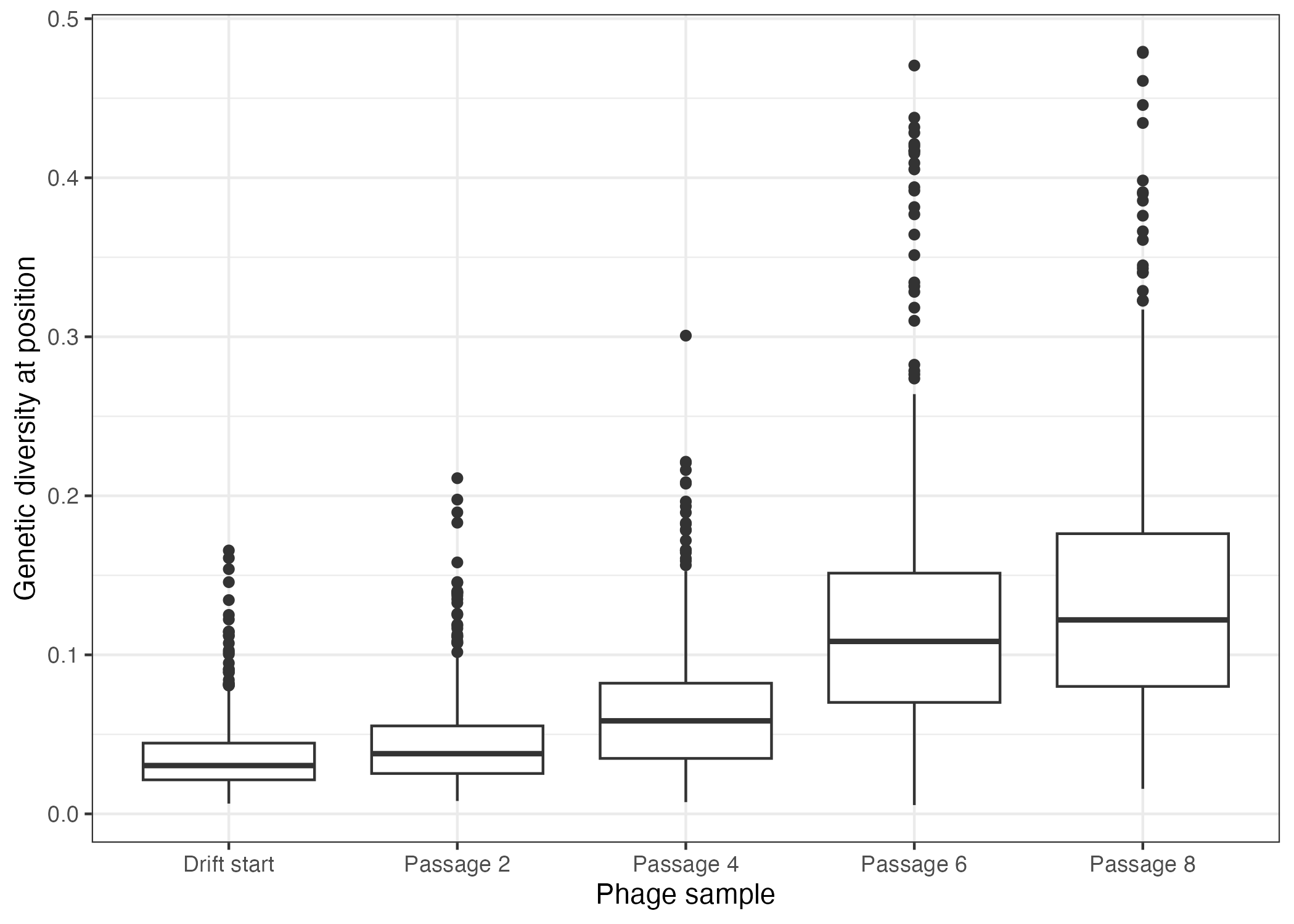

During PACE, both phages and infected bacteria are continuously removed from the lagoon. If phages propagate too slowly there's a risk that all the phages could be washed out before they can replicate and evolve. This is especially risky at the start of the experiment, when the initial activity of the E3 ligase may be too low to maintain sufficient phage propagation. To mitigate this risk, a process called "drift" is used before the evolution starts. Drift allows random mutations to occur without any selection pressure, increasing the genetic diversity among the phages. This genetic variability helps prevent phage washout by giving the population a better chance of harbouring variants with higher activity that can sustain propagation in the lagoon.

To this end, we propagated the SIAH1 SP phages in bacterial cells that contain a special drift plasmid (DP6). The DP6 plasmid not only increases the mutation rate but also supplies the necessary pIII protein, allowing phages to replicate regardless of the E3 ligase's activity. Over eight infection and growth cycles (called passages), we sequenced the SIAH1 SP phages and estimated the amount of mutations at different positions in the SIAH1 gene. With each passage, we saw the number of mutated phages increase, creating a highly diverse pool of SIAH1 SP phages. This pool can then serve as a robust starting pool for the next stages of evolutionary experiments, reducing the risk of phage washout and enhancing the chances of evolving phages with improved E3 ligase activity.

What are the next steps?

Once we confirm that the E3-dependent phage propagation system is working properly, we will gradually evolve SIAH1/2 with PACE from recognizing the native degron to recognizing the degron of the final target protein, NLRP3. This process, called a "substrate walk," will help us evolve the SIAH1/2 enzymes to specifically recognize and mark NLRP3 for degradation. If we are successful in finding a variant of SIAH1/2 that can target NLRP3, we will test its effects in mammalian cells to see if it can trigger the degradation of NLRP3 through a process called polyubiquitination. Importantly, we'll also test for any unwanted effects (off-target effects) of the SIAH1/2 variants and, if they occur, remove them in further rounds of evolution using the negative selection system introduced above. While we continue to fine-tune the selection system, we believe this method holds promise for developing new therapies using engineered enzymes as targeted protein degradation drugs.

References

-

Qi J, Kim H, Scortegagna M, Ronai ZA. Regulators and Effectors of Siah Ubiquitin Ligases. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;67: 15–24. doi:10.1007/s12013-013-9636-2 ↩

-

Pérez M, García-Limones C, Zapico I, Marina A, Schmitz ML, Muñoz E, et al. Mutual regulation between SIAH2 and DYRK2 controls hypoxic and genotoxic signaling pathways. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;4: 316–330. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjs047 ↩

-

Zhang Q, Wang Z, Hou F, Harding R, Huang X, Dong A, et al. The substrate binding domains of human SIAH E3 ubiquitin ligases are now crystal clear. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2017;1861: 3095–3105. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.10.019 ↩

-

Levin-Kravets O, Tanner N, Shohat N, Attali I, Keren-Kaplan T, Shusterman A, et al. A bacterial genetic selection system for ubiquitylation cascade discovery. Nat Methods. 2016;13: 945–952. doi:10.1038/nmeth.4003 ↩

-

Stebbins JL, Santelli E, Feng Y, De SK, Purves A, Motamedchaboki K, et al. Structure-Based Design of Covalent Siah Inhibitors. Chemistry & Biology. 2013;20: 973–982. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.008 ↩

-

Santelli E, Leone M, Li C, Fukushima T, Preece NE, Olson AJ, et al. Structural Analysis of Siah1-Siah-interacting Protein Interactions and Insights into the Assembly of an E3 Ligase Multiprotein Complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280: 34278–34287. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506707200 ↩↩

-

House CM, Hancock NC, Möller A, Cromer BA, Fedorov V, Bowtell DDL, et al. Elucidation of the Substrate Binding Site of Siah Ubiquitin Ligase. Structure. 2006;14: 695–701. doi:10.1016/j.str.2005.12.013 ↩

-

Briant DJ, Ceccarelli DF, Sicheri F. I Siah Substrate! Structure. 2006;14: 627–628. doi:10.1016/j.str.2006.03.003 ↩

-

House CM, Frew IJ, Huang H-L, Wiche G, Traficante N, Nice E, et al. A binding motif for Siah ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100: 3101–3106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0534783100 ↩

-

Liang Z, Damianou A, Di Daniel E, Kessler BM. Inflammasome activation controlled by the interplay between post-translational modifications: emerging drug target opportunities. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19: 23. doi:10.1186/s12964-020-00688-6 ↩

-

Li Z, Chen S, Jhong J-H, Pang Y, Huang K-Y, Li S, et al. UbiNet 2.0: a verified, classified, annotated and updated database of E3 ubiquitin ligase–substrate interactions. Database. 2021;2021: baab010. doi:10.1093/database/baab010 ↩

-

Wang X, Li Y, He M, Kong X, Jiang P, Liu X, et al. UbiBrowser 2.0: a comprehensive resource for proteome-wide known and predicted ubiquitin ligase/deubiquitinase–substrate interactions in eukaryotic species. Nucleic Acids Research. 2022;50: D719–D728. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab962 ↩