Background

Proteins Gone Rogue: How Misbehaving Proteins Drive Disease

Virtually all processes in our cells rely on the proper functioning of macromolecules called proteins. They are composed of long chains of amino acids, with the precise sequence of amino acids determining the three-dimensional structure and function of the protein. Proteins provide structural support for cells, replicate genetic material, process metabolic reactions, generate energy, and contribute to cell growth, among countless other vital roles. However, maintaining the proper activity and behaviour of these proteins is crucial for cellular health.

Due to factors such as ageing, genetic mutations, or environmental stressors, proteins can malfunction, leading to detrimental effects. Proteins might be overproduced, misfolded, or become hyperactive, contributing to cellular dysfunction and disease. This dysregulation of protein activity is a growing concern, as it underlies many serious health issues. We can illustrate this with two prominent examples: hepatic diseases, like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Both conditions are increasingly prevalent and represent a major health burden worldwide, largely due to the accumulation or overactivity of harmful proteins that disrupt normal cellular processes.

The Rise of Fatty Liver Disease

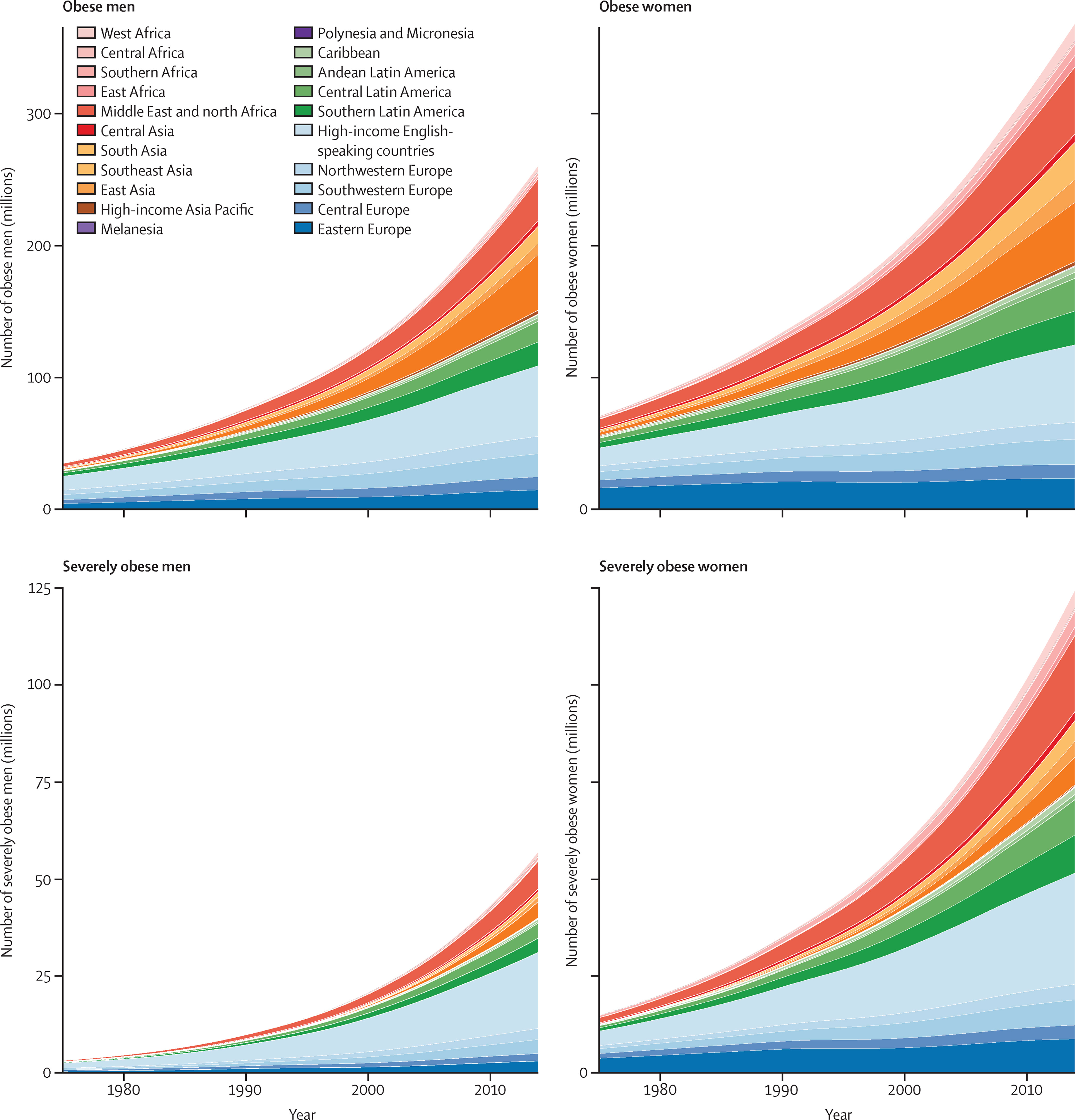

In recent decades, growing global wealth and improved food availability have led to increased consumption of calorie-dense, highly processed foods. This shift in dietary habits, combined with a decrease in physical activity due to more urbanised, sedentary lifestyles, has contributed to rising rates of obesity and metabolic disorders (Figure 1). Currently, more than 1.9 billion adults are overweight, with 650 million classified as obese. Obesity is a major risk factor for both type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), with an estimated 77.87% of obese individuals developing NAFLD2. Globally, NAFLD has an estimated prevalence of 30%, making it one of the most common liver disorders worldwide3.

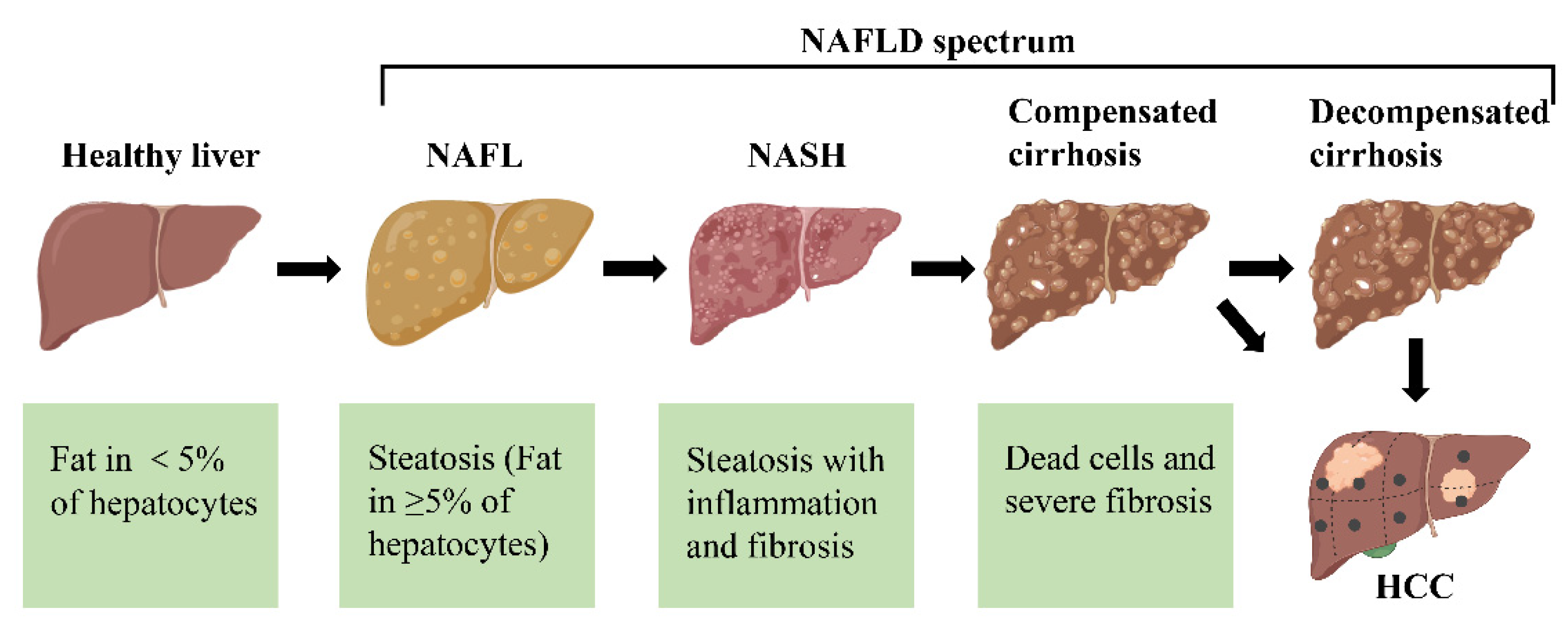

NAFLD progresses through several stages, potentially leading to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Figure 2). In the first stage of NAFLD, known as simple fatty liver (steatosis), fat accumulates in liver cells without causing harm. This stage is usually asymptomatic and can be reversed with lifestyle changes. If left untreated, NAFLD may advance to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a more severe form involving liver inflammation and potential cell damage. Persistent NASH can lead to fibrosis, where scar tissue forms around the liver and its vessels, though the liver may still function relatively well. Over time, fibrosis can progress to cirrhosis, which is marked by extensive scarring and impaired liver function, eventually leading to liver failure. In some severe cases, NAFLD can progress to HCC, a form of liver cancer that may arise even in non-cirrhotic patients, though it is more common in those with cirrhosis. Importantly, not all individuals with NAFLD will progress through every stage, and early intervention can prevent or even reverse disease progression4. Targeting NAFLD is crucial due to its widespread prevalence, lack of effective treatments, and increasing economic burden. NAFLD affects around 30% of the global population, yet there are currently no FDA-approved medications specifically for its treatment. Developing new therapies would address this significant treatment gap, potentially improving patient outcomes by preventing disease progression. Effective interventions could also reduce the economic strain associated with managing advanced stages of NAFLD, which require costly care.

Toward Better Solutions for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Thanks to medical and technological advancements, we are living longer, but this has led to an increase in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Huntington's, and Parkinson's. In Switzerland alone, dementia-related diseases incurred costs of 13.74 billion USD in 20176, and globally, the number of cases is expected to rise to 135 million by 20507. This growing burden highlights the urgent need for innovative and effective solutions. Despite decades of research, most current therapies focus on managing symptoms rather than curing the diseases. For example, traditional pharmacological therapies, like cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's and dopamine agonists for Parkinson's, aim to manage symptoms without addressing the root causes89.

Non-pharmacological interventions—such as rehabilitation, brain stimulation, and cognitive training—can improve quality of life but do not halt disease progression. Promising new approaches include antibody-based therapies, which aim to neutralise disease-associated proteins by promoting their clearance and preventing their aggregation and spread. However, this strategy faces significant challenges. Antibodies are large molecules that struggle to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, meaning they primarily target extracellular protein deposits, leaving the toxic protein accumulations inside cells unaddressed. Given these limitations, there is a pressing need for more innovative approaches that can effectively target the underlying causes of neurodegenerative diseases.

NLRP3: A Key Player in Chronic Disease and Inflammation

A common factor between these two chronic diseases is the role of NLRP3. NLRP3 acts as an intracellular danger sensor, helping defend against pathogens. When activated by danger signals, it forms an inflammasome and triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, causing inflammation in surrounding tissues. Additionally, NLRP3 activation can lead to cell death, contributing to the progression of these diseases. This makes NLRP3 a key player in the immune system and a strong driver of inflammation11.

Although NLRP3 plays a beneficial role in immunity, its overactivation is linked to many autoinflammatory conditions, including liver diseases like nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and neurodegenerative disorders12. Triggers for NLRP3 overactivation include factors like reactive oxygen species, gut imbalances, cardiolipin, and cholesterol crystals13. Our goal is to develop a therapy to reduce NLRP3 activity in patients affected by these liver and neurodegenerative diseases, helping to slow down inflammation-driven disease progression.

Targeted Protein Degradation presents a promising therapeutic strategy

Cells not only constantly produce proteins, but also continuously break down old, damaged, or unnecessary ones. This protein degradation process is vital for maintaining cellular health and is often centred around ubiquitination—a system where unwanted proteins are tagged with a small molecule called ubiquitin. The presence of ubiquitin signals to the cell’s "garbage disposal" system, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), to degrade these proteins14.

The UPS involves several important steps and enzymes to ensure that only the right proteins are marked for destruction. Here, three enzymes are involved in the tagging process: Ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and E3 ligases. In humans, the UBA1 enzyme (E1) usually starts the process by attaching ubiquitin to one of about 40 E2 enzymes. The E3 ligase then plays a critical role, acting as a "scout" that identifies which protein needs to be degraded by recognizing different signals, such as specific peptide sequences called degrons, on the target protein. After recognition the first ubiquitin molecule is attached to the target, initiating the formation of a polyubiquitin chain. This can mark the protein for degradation in the proteasome15, where proteins are broken down into smaller pieces for reuse or disposal1617.

The UPS is highly selective, ensuring that only the right proteins are degraded. However, sometimes this system fails to properly address problematic proteins, which can lead to diseases, such as cancer or autoimmune diseases1819. To overcome this, researchers have turned to Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD), a cutting-edge therapeutic approach that directs the body’s own degradation machinery toward disease-causing proteins. Current TPD strategies include small molecules like PROTACs (proteolysis-targeting chimaeras) and molecular glues, which help guide harmful proteins to be tagged with ubiquitin and destroyed by the UPS14.

Despite their promise, current TPD methods face significant challenges. They can mistakenly tag healthy proteins for degradation, leading to unwanted off-target effects. Furthermore, these approaches may be inherently toxic or suffer from poor pharmacokinetic properties, complicating their development into safe and effective treatments20. These limitations underscore the need for novel advancements to improve the precision of targeting harmful proteins, which could greatly enhance both the effectiveness and safety of protein degradation therapies.

Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution

Life on earth was shaped by evolution by which the different species adapted to their environment over the course of countless generations and millions of years. In the lab, it is possible to speed up this process and guide it towards a user-defined goal, which is called directed evolution. Here, the goal is usually to steer proteins or nucleic acids towards adapting new functions or improve their main features like the catalysis of a certain reaction. Directed evolution of biomolecules generally involves three main steps. First, we take the molecule of interest and introduce mutations—small changes that have the potential to improve, or impair, its function. From this pool of mutants, we then need to identify those that perform better, either by screening—measuring how well they carry out their function, and picking those that perform best—or by selection, where only the mutants that perform their function well enough are allowed to pass. Finally, once we've identified promising variants, we repeat the cycle again and again. If this sounds like a long and tedious process, that's because it is. Each of these steps can take several days, requiring the constant attention of scientists.

To make directed evolution more efficient without compromising any steps, researchers have turned to a natural system that thrives on mutation, selection, and iteration—viruses. More specifically, the spotlight is on viruses that infect bacteria, known as bacteriophages. Like viruses that infect humans and animals, bacteriophages invade their host cells, hijack the bacterial machinery, and produce new viral particles to continue the infection cycle. During replication, some phages naturally acquire mutations because the bacterial replication process is prone to errors. For example, the bacteriophage M13, which infects E. coli (a common model bacterium), generates a mutation in about 1 out of every 200 phages due to these replication errors21.

Now, imagine if we could link the replication of a phage to the activity of our biomolecule of interest. We could then leverage the phage's natural traits to drive the continuous evolution of the biomolecule. Phages carrying better-performing variants would replicate faster, infect more bacteria, and increase the presence of those improved variants. Meanwhile, the replication errors would ensure that new variants constantly enter the evolutionary race.

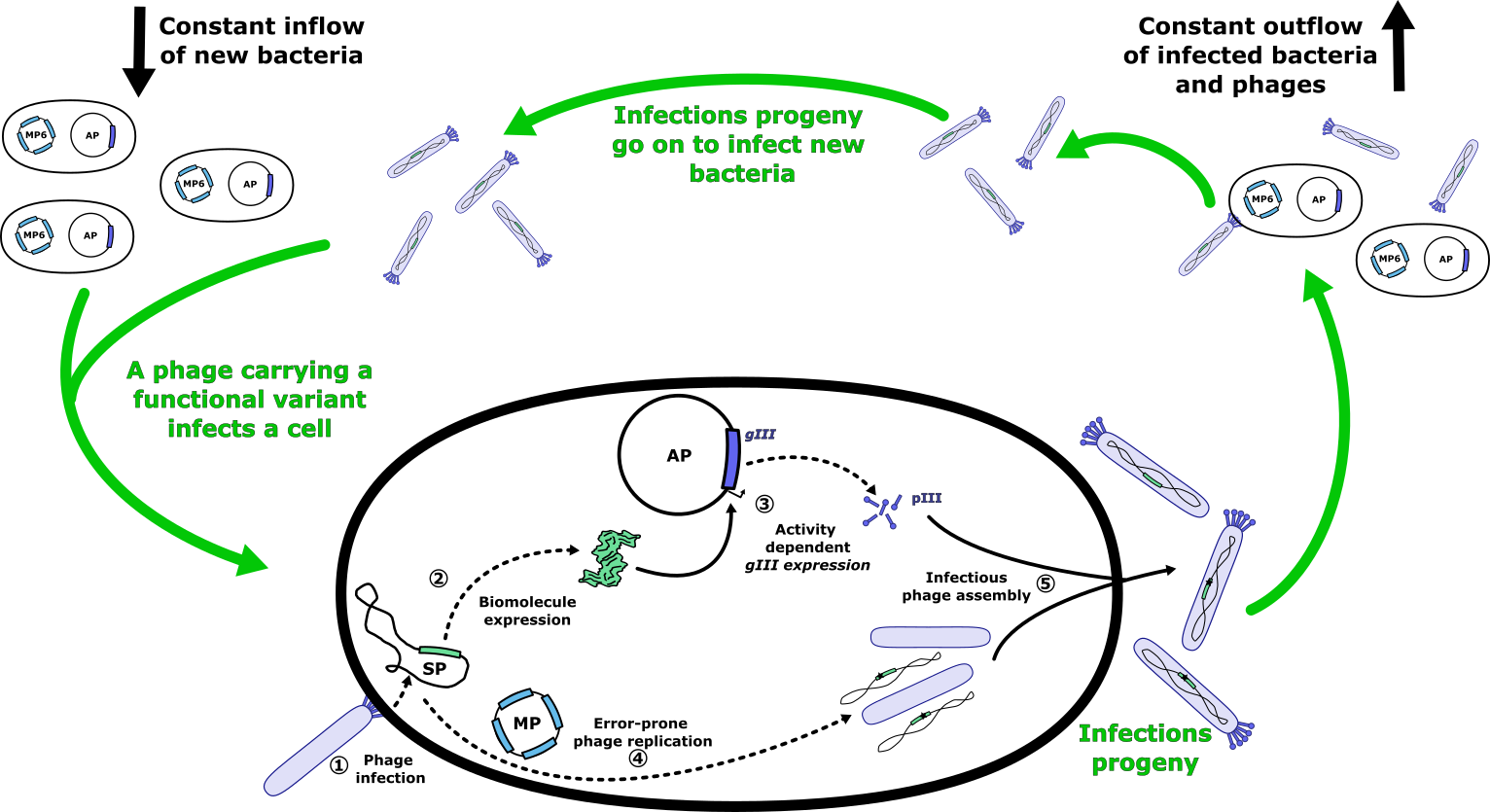

Fortunately, scientists figured out how to do this back in 2011 creating the Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) approach and sparing us the need to reinvent the wheel22. They used the fact that M13 phage needs a specific protein, pIII, to infect bacteria. Phages without pIII replicate poorly, while those that produce more pIII generate more infectious particles. This created an opportunity: by coupling the activity of our biomolecule to pIII production, phages carrying more active biomolecule variants would produce more pIII and, as a result, replicate more efficiently.

The key to this system is linking the activity of the biomolecule to the expression of a gene coding for pIII (Figure 4). This challenge, central to synthetic biology, has been successfully addressed for a range of biomolecular functions, including DNA, RNA, and protein binding, as well as enzyme activity2324. To achieve this, we use an accessory plasmid (AP), which carries a regulatory circuit that ties the biomolecule’s activity to the expression of pIII. This plasmid is placed in the host bacteria, allowing for controlled expression of pIII based on the biomolecule's performance. At the same time, we introduce the gene encoding the biomolecule of interest into the genome of the phage, which we call a selection phage (SP). To ensure that only phages with active biomolecules can propagate, we remove the native gene for pIII from the phage genome. This means the phage can only replicate if the biomolecule inside the phage activates the regulatory circuit in the host cell, leading to pIII production. This clever setup ensures that only phages carrying functional or improved biomolecule variants can replicate and propagate, effectively driving the selection process.

To make this a self-sustaining evolution system, a few more adjustments are needed. We provide the phages with a steady supply of fresh bacteria in a "lagoon" - a chamber where bacteria and phages grow. This ensures that newly generated phages always have hosts to infect. Simultaneously, we flush out old bacteria and phages, ensuring that only those phages that replicate quickly enough can survive. In this setup, better-performing variants will thrive and outcompete others, driving evolution forward. To speed up this process, a special mutation plasmid (MP) is introduced into the bacteria. This plasmid increases the already high mutation rate of the phages, significantly accelerating the pace of evolution and allowing researchers to quickly refine biomolecules. Over time, phages with beneficial mutations accumulate and become dominant in the population. These mutations can then be identified by sequencing the phages. Finally, one often uses orthogonal methods to confirm the activity of the evolved biomolecule.

Sometimes, the activity of the biomolecule we're evolving is too weak, resulting in slow phage propagation that makes it difficult to run PACE effectively. In such cases, we use a modified approach called Phage-Assisted Non-Continuous Evolution (PANCE). Unlike PACE, where phages and bacteria are continuously refreshed in a bioreactor (lagoon), PANCE works in a batch culture. In this method, phages are introduced into a batch of bacteria and allowed to propagate over a set period. Once the cycle is complete, a sample of the culture is taken and used to inoculate a new batch of bacteria, repeating the process. This non-continuous setup eliminates the risk of phages being removed from the culture faster than they can propagate, enabling evolution even when the activity of the biomolecule is low. PANCE is often used as a preliminary step before PACE, allowing us to first evolve the biomolecule to a higher activity level, which is then sufficient for running continuous evolution in the PACE system.

References

-

Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. The Lancet. 2016;387: 1377–1396. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X ↩

-

Dharmalingam M, Yamasandhi Pg. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2018;22: 421. doi:10.4103/ijem.IJEM_585_17 ↩

-

Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77: 1335–1347. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004 ↩

-

Grander C, Grabherr F, Tilg H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: pathophysiological concepts and treatment options. Cardiovascular Research. 2023;119: 1787–1798. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvad095 ↩

-

Guo X, Yin X, Liu Z, Wang J. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Pathogenesis and Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment. IJMS. 2022;23: 15489. doi:10.3390/ijms232415489 ↩

-

Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019;15: 321–387. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010 ↩

-

Gammon K. Neurodegenerative disease: Brain windfall. Nature. 2014;515: 299–300. doi:10.1038/nj7526-299a ↩

-

Birks JS, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001190.pub3 ↩

-

Cummings J, Aisen PS, DuBois B, Frölich L, Jack CR, Jones RW, et al. Drug development in Alzheimer’s disease: the path to 2025. Alz Res Therapy. 2016;8: 39. doi:10.1186/s13195-016-0207-9 ↩

-

Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7: e105–e125. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 ↩

-

Mangan MSJ, Olhava EJ, Roush WR, Seidel HM, Glick GD, Latz E. Erratum: Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17: 688–688. doi:10.1038/nrd.2018.149 ↩

-

Yao J, Wang Z, Song W, Zhang Y. Targeting NLRP3 inflammasome for neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28: 4512–4527. doi:10.1038/s41380-023-02239-0 ↩

-

Ramos-Tovar E, Muriel P. NLRP3 inflammasome in hepatic diseases: A pharmacological target. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2023;217: 115861. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115861 ↩

-

Tsai JM, Nowak RP, Ebert BL, Fischer ES. Targeted protein degradation: from mechanisms to clinic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25: 740–757. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00729-9 ↩↩

-

Cowan AD, Ciulli A. Driving E3 ligase substrate specificity for targeted protein degradation: Lessons from nature and the laboratory. Annu Rev Biochem. 2022;91: 295–319. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-032620-104421 ↩

-

Rape M. Ubiquitylation at the crossroads of development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;19: 59–70. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.83 ↩

-

Damgaard RB. The ubiquitin system: from cell signalling to disease biology and new therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28: 423–426. doi:10.1038/s41418-020-00703-w ↩

-

Vu PK, Sakamoto KM. Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and human disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;71: 261–266. doi:10.1006/mgme.2000.3058 ↩

-

Martínez-Jiménez F, Muiños F, López-Arribillaga E, Lopez-Bigas N, Gonzalez-Perez A. Systematic analysis of alterations in the ubiquitin proteolysis system reveals its contribution to driver mutations in cancer. Nat Cancer. 2020;1: 122–135. doi:10.1038/s43018-019-0001-2 ↩

-

Békés M, Langley DR, Crews CM. PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21: 181–200. doi:10.1038/s41573-021-00371-6 ↩

-

Cuevas JM, Duffy S, Sanjuán R. Point Mutation Rate of Bacteriophage ΦX174. Genetics. 2009;183: 747–749. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.106005 ↩

-

Esvelt KM, Carlson JC, Liu DR. A system for the continuous directed evolution of biomolecules. Nature. 2011;472: 499–503. doi:10.1038/nature09929 ↩

-

Vidal M. Yeast forward and reverse ’n’-hybrid systems. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27: 919–929. doi:10.1093/nar/27.4.919 ↩

-

Baker K, Bleczinski C, Lin H, Salazar-Jimenez G, Sengupta D, Krane S, et al. Chemical complementation: A reaction-independent genetic assay for enzyme catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99: 16537–16542. doi:10.1073/pnas.262420099 ↩